Film vs. Digital

I’m often asked if film, actual celluloid, is better than digital photography. I would easily say the correct characterization of film is uniquely different, not better. Regarding sharpness and ability to reproduce, most photographers ten years back would agree that digital sensors where no match against traditional film; the technology just wasn’t there yet. Fast forward to today, digital sensor technologies, with their proprietary processing algorithms, have come a long way and unquestionably provide sharper looking images compared to film. However, there are certain qualities of film that digital cannot match.

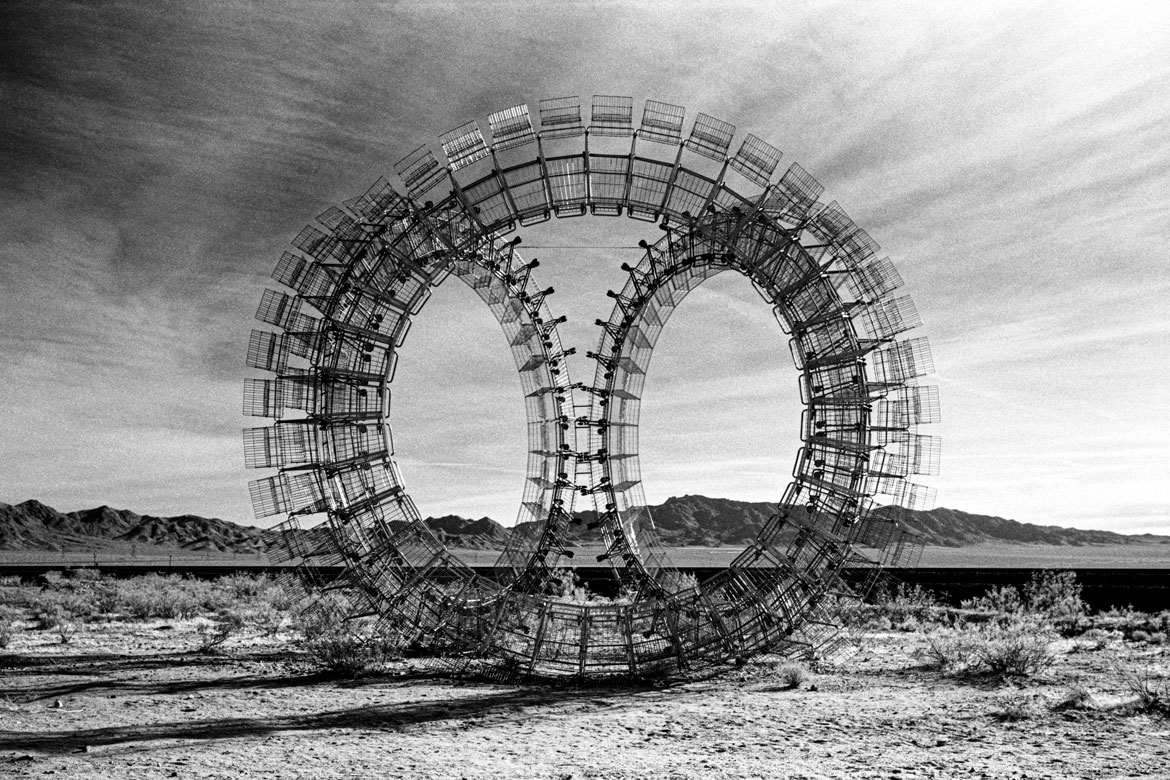

Film has a light sensitive photo chemical emulsion, possessing a three dimensional grain structure and infinite in the breadth of its molecular composition (think of no two grains of sand being alike), whereas digital sensors are comprised of identically sized pixels calculated inside a finite grid. For my commercial food and architectural photography work in Las Vegas, I prefer digital for this simple reason; my clients want me to capture their product, so their customers can best experience it online, or in print, when deciding on where to visit. They want an image that is as close to the real thing as possible, not an interpretation. The other reason for digital is its speed and the ability to image stack, should layer masking need to be performed. Yes, in theory you could stack film images in Photoshop for layer masking, but even if the camera were locked in place, on a tripod, the film still shifts slightly when lever advanced; digital sensors never move. Layer masking film images will always result with slight register alignment issues.

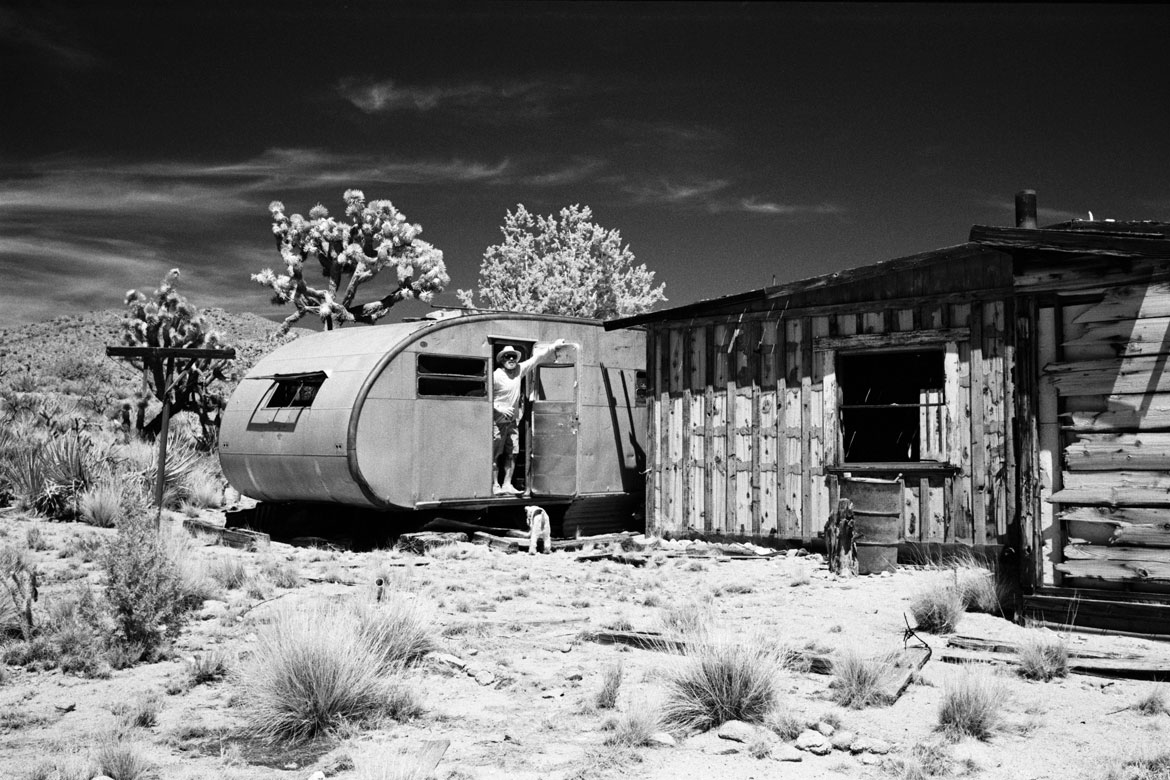

So, with digital photography dominating the market, why still bother with film? After all, film is time consuming in that you have to purchase it for each instance of use and then pay reciprocally on the back end for development. You can certainly develop the film yourself to save money, but that involves the tedious handling of the medium in total darkness, mixing & storing of chemicals, drying time, cutting & sleeving and should you want to share the images electronically…scanning to a digital file. For storage, you’ll need air-tight archival ring binders and space in the closet that maintains a suitable temperature for the foreseeable future. With digital, you can store your entire life on one tiny flash drive.

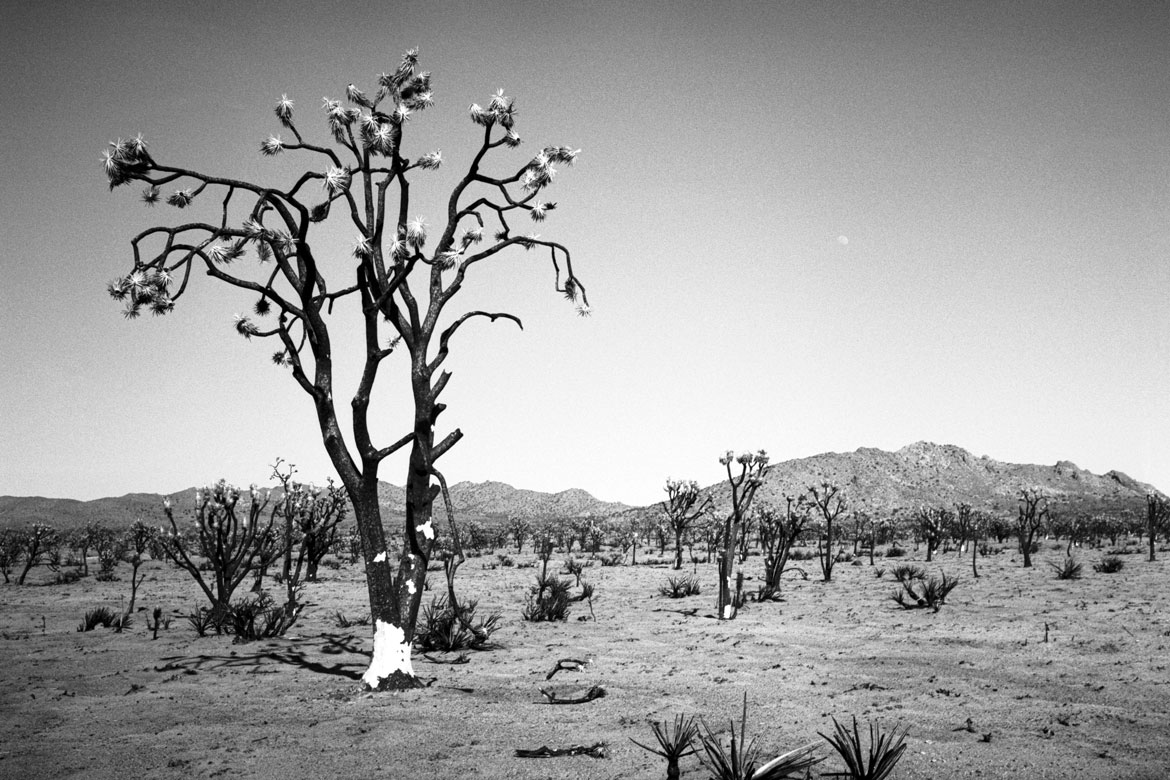

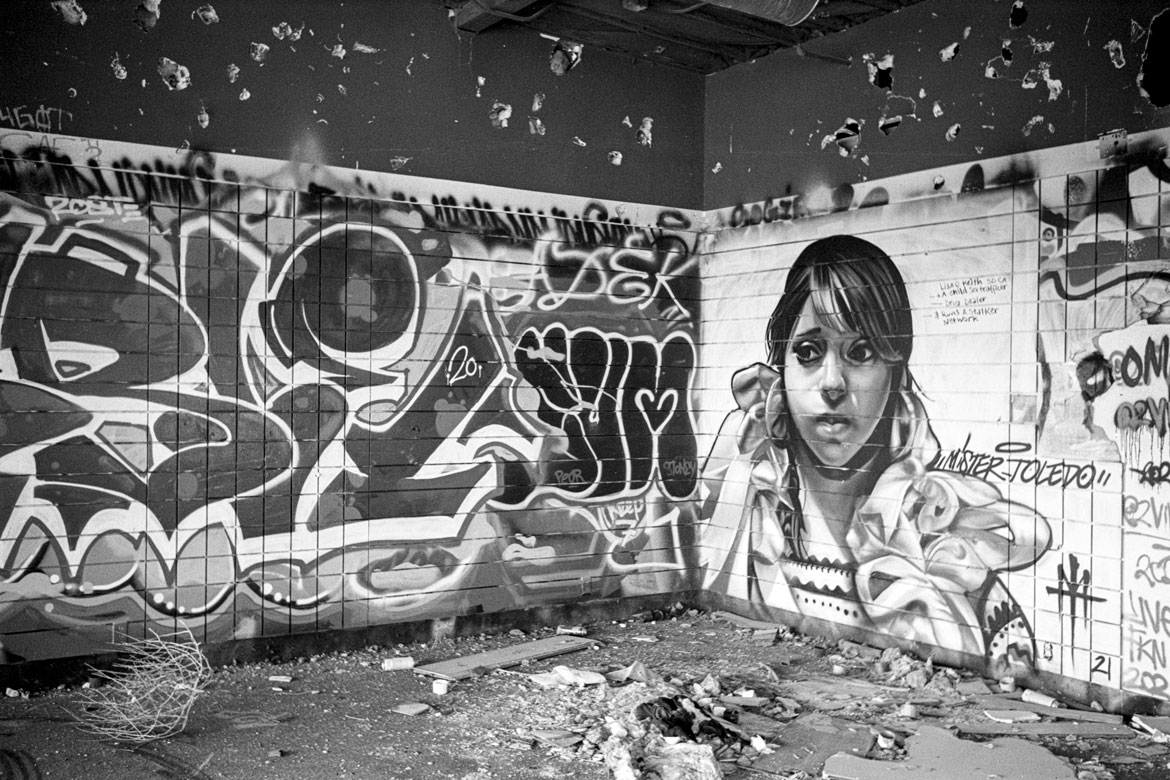

The point that gets lost is that film is an art, with a specific look that digital cannot reproduce. Yes, with the tap of an icon and the use of a thumb slider on our smartphones, we can add/subtract grain, apply faux vignetting and sepia tone for good measure too. That’s great, and I occasionally use those filters as well to add style, but there is no substitute for the authenticity of celluloid. In my life's travels, I prefer film when capturing memorable moments and places for a specific reason. Only film can give you that much desired, atmospheric and ingrained look.